Five reasons why we are entering the next copper supercycle

A ‘commodity supercycle’ is a period of consistent price increases that lasts for more than five years, and in some cases, decades. The Bank of Canada defines it as an “extended period during which commodity prices are well above or below their long-term trend.”

Supercycles arise because of the long lag between commodity price signals and changes in supply. Although each commodity is different, the following is a summary of a typical boom-bust cycle:

As economies grow, the demand for raw materials increases, and eventually demand exceeds supply. This leads to rising commodity prices, but commodity producers do not initially react to the higher prices because they are unsure whether they will last. As a result, the gap between demand and supply continues to widen, keeping upward pressure on prices.

Eventually, prices become so attractive that producers respond by making additional investments to increase supply, reducing supply and demand. High prices continue to encourage investment until supply finally outstrips demand, putting downward pressure on prices. But even as prices fall, supply continues to rise as investments made during the boom bear fruit. Scarcity turns into abundance and commodities enter the bearish part of the cycle.

There have been several commodity supercycles throughout history. The last one started in 1996 and peaked in 2011, driven by the demand for raw materials from the rapid industrialization taking place in markets like Brazil, India, Russia and especially China.

We can talk about the cyclical nature of commodities in general, but we can also select certain commodities to see if they are on the rise or in decline.

Sprott recently did so, pointing out that a new copper supercycle is emerging, built on several rising geopolitical and market trends, including electrification, national security concerns, environmental policies, supply constraints and deglobalization.

We agree. Below are five reasons why we are entering the next copper supercycle.

Demand is rising

Copper is one of the most important metals with more than 20 million tons consumed each year in a variety of industries, including building construction (wires and pipelines), power generation/transmission and electronic product manufacturing.

In recent years, the global shift to clean energy has further stretched the need for base metals. Simply put, electrification does not happen without copper, the heartbeat of the global energy economy.

Along with the usual applications in building wiring and plumbing, transportation, power transmission and communications, demand for copper in electric vehicles and renewable energy systems is now increasing.

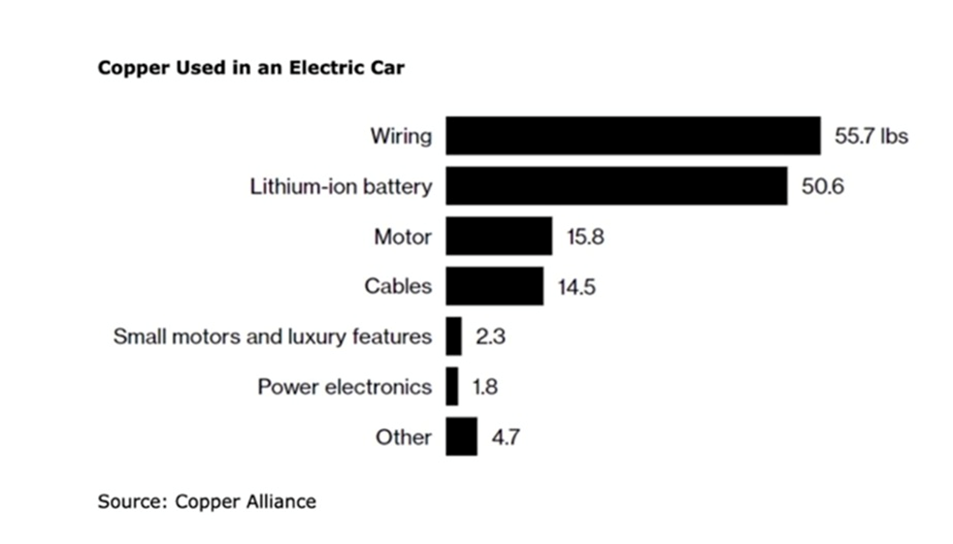

Millions of meters of copper wires will be needed to strengthen the world’s electricity grid, and hundreds of thousands of tons more are needed to build wind and solar farms. Electric vehicles use triple the amount of copper as gasoline-powered cars. There are more than 180 kg of copper in the average home.

Millions of meters of copper wires will be needed to strengthen the world’s electricity grid, and hundreds of thousands of tons more are needed to build wind and solar farms. Electric vehicles use triple the amount of copper as gasoline-powered cars. There are more than 180 kg of copper in the average home.

Additional copper is demanded by the electrification of public transport systems, 5G and AI.

Supply shortage

But some of the world’s largest mining companies, market analysts and banks, warn that by 2025 there will be a massive shortfall in copper, now the world’s most critical metal because of its important role in the green economy.

The deficit will be so large, noted The Financial Post, that it could hold back global growth, drive up inflation by raising manufacturing costs and throw global climate targets off course.

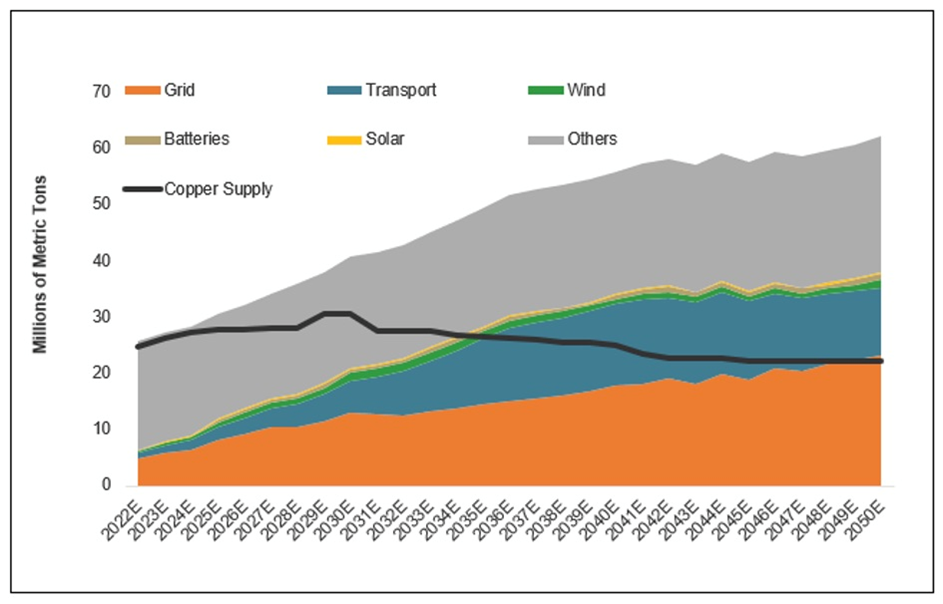

The graph below shows supply not keeping up with demand. Two reasons identified by Sprott: developing a new copper mine is long and expensive, often taking over a decade from exploration to production; and the mining sector has seen long periods of underinvestment, when low copper prices meant reduced exploration budgets and fewer discoveries.

There has also been an over-reliance on mergers and acquisitions. It is much easier for a copper mining company to increase its reserves by buying a smaller company (and its reserves) than to devote capital to greenfield exploration, which is expensive and risky.

According to Sprott, relying on M&A over new discoveries could slow the industry’s supply response to price signals and lead to prolonged market tightness, supporting a bullish outlook for the copper market.

Source: BloombergNEF Transition Metals Outlook 2023. The black line represents supply and the shaded areas represent demand. The demand is based on a net-zero scenario, i.e. global net-zero emissions by 2050 to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

Source: BloombergNEF Transition Metals Outlook 2023. The black line represents supply and the shaded areas represent demand. The demand is based on a net-zero scenario, i.e. global net-zero emissions by 2050 to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

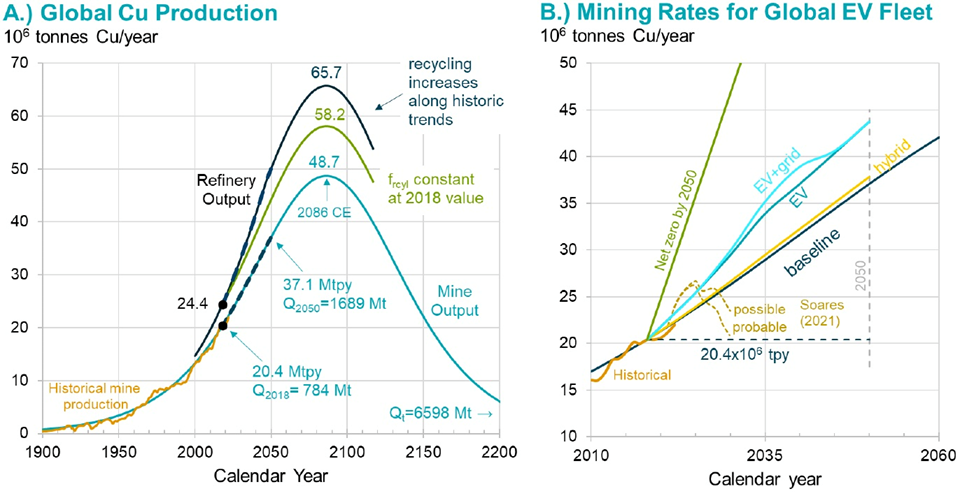

The extent to which the industry has failed to create new mines is revealed by a new study from the University of Michigan and Cornell University. The researchers found that copper cannot be mined fast enough to keep up with current US policies to make the transition from fossil fuel power and transportation to electric vehicles and renewable energy.

The Inflation Reduction Act, for example, requires 100% of new cars to be electric vehicles by 2035.

“A normal Honda Accord needs about 20 kg of copper. The same battery electric Honda Accord needs almost 100 kg of copper. Onshore wind turbines require about 10 tons of copper, and in offshore wind turbines that amount can more than double,” said Adam Simon, co-author of the paper, published by the International Energy Forum (IEF). “We show in the paper that the amount of copper needed is basically impossible for mining companies to produce.”

How impossible? The researchers found that between 2018 and 2050, the world will need to mine 115% more copper than has been mined in all of human history up to 2018. This would meet our current copper needs and support developing countries without taking into account the green energy transition.

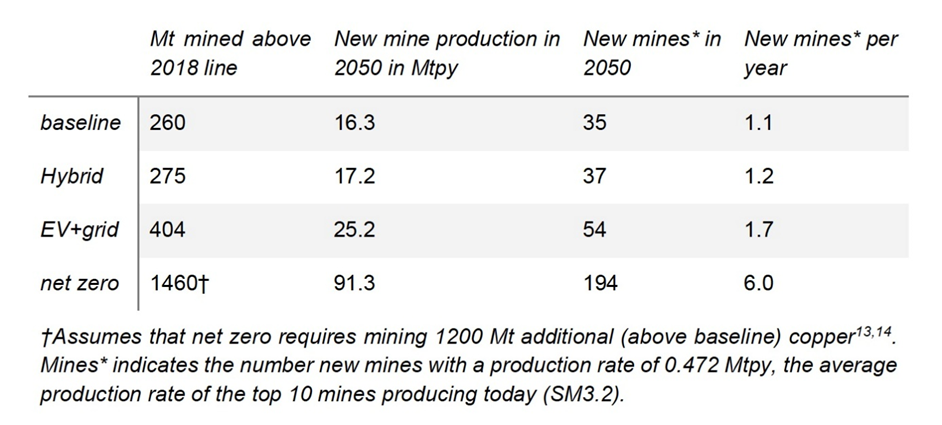

To electrify the global vehicle fleet, 55% more new mines need to be brought into production. Between 35 and 195 large new copper mines would need to be built over the next 32 years, at a rate of up to six mines per year. In other words, impossible. In highly regulated environments like the US and Canada, it can take up to 20 years to build a mine from scratch.

Source: International Energy Forum

Source: International Energy Forum

Source: International Energy Forum

Source: International Energy Forum

Instead of fully electrifying the US vehicle fleet, Simon suggests focusing on manufacturing hybrid vehicles, which require much less copper than electric vehicles – 29 kg versus 60 kg.

Going this route would not require major grid improvements and would have almost as much impact on reducing CO2 emissions, the study found. The likelihood of finding the copper needed to make hybrids is also much higher than for electric vehicles.

Almost 600,000 tons of copper supply did not reach the market last year due to the closure of Cobre Panama by the Panamanian government and a strike at the Las Bambas copper mine in Peru.

Anglo-American says its Chilean production for 2024 will disappoint, at between 210,000 and 270,000 tons due to grade reductions and logistical problems at the Los Bronces mine. (Goehring & Rozencwajg)

Chile’s copper production has been dented by a prolonged drought in the country’s arid north. Codelco’s production in 2023 was the lowest in 25 years. Chile in April recorded its lowest month of copper production in more than a year, as far as the world’s largest copper producer is concerned. Mines produced 6.7% less than in March and 1.5% less than in April 2023.

Resource nationalism

The term ‘resource nationalism’ is loosely defined as the tendency of people and governments to assert control over natural resources located on their territory for strategic and economic reasons.

While it provides opportunities for those in less developed countries to seek profit from their natural resources, state ownership can exacerbate the instability of the world’s critical mineral wealth.

The Sprott report notes that export bans and tariffs, political instability and increasing resource nationalism in copper-producing regions can disrupt supply chains and cost structures, leading to price increases.

De-globalization and rising geopolitical tensions are increasing dependence on local supply chains and boosting military spending, stimulating demand for copper.

Two recent examples of copper resource nationalism took place in Peru and Panama.

In 2023, the world’s second-largest copper producer was plagued by protests due to a change of government. Last November, a strike at the Las Bambas copper mine threatened ~250,000 tons of annual production.

Also late last year, the Panamanian government ordered First Quantum Minerals to close its Cobre Panama operations, removing almost 350,000 tons of copper from global supply.

Environmental problems

The transition to clean energy aims to clean up air pollution. Copper is one of the main metals needed to drive this transition, yet environmental concerns often stand in the way of new mines.

“Copper producers face stringent environmental regulations related to land use, pollution control and conservation. These can potentially delay new projects,” the Sprott report notes.

In a recent article, Barron’s points to the National Environmental Policy Act as one piece of legislation that makes the permitting process for large mining and energy infrastructure projects difficult to navigate. While the Biden administration and congressional leaders are trying to reform the permitting process, Barron notes that it won’t help the mining projects that entered permitting before the new one- to two-year time limits were put in place. This includes the Resolution copper mine in Arizona, the Rhyolite Ridge lithium drill project and the Stibnite gold project.

Inflation

A rally in May took copper prices to a record high of $5.20/lb. Despite a recent pullback, prices are 13% higher so far this year amid speculative bets on looming shortages. (Trade economics)

The Federal Reserve this week froze interest rates at the current 5.25-5.5% and said there was likely to be only one quarter rate cut by the end of the year instead of two. Inflation fell by two-tenths of a percentage point in May (3.6%) compared with April (3.4%) – still far from the Fed’s 2% target.

According to gold and copper bull Peter Schiff, high inflation and a lack of supply are conspiring with increased demand for electric vehicles, a boom in renewable energy technologies and an AI bubble to keep prices up even without the flood of speculative money.

Schiff believes that even if impractical “net zero” targets are revised down to more realistic figures, the demand will still be there, and the current supply pressures and inflationary pressures are here to stay…

To avoid a banking and commercial real estate crisis, the Fed has no choice but to cut interest rates at some point. This will invite a new stream of inflationary expansion as the Fed ignores the pressure cooker its policies helped create.

Conclusion

All of the above can only mean one thing for copper: higher prices.

We have already mentioned the closure of Cobre Panama, a major strike in Peru and production losses in Chile contributing to supply problems.

All four of Codelco’s mega-projects have been delayed by years, suffered cost overruns totaling billions, and suffered accidents and operational problems while failing to deliver the promised increase in production, according to the company’s own projections.

There are also concerns for Zambia, Africa’s second largest copper producer, where the drought has lowered dam levels, creating a power crisis that threatens the country’s planned copper expansion.

Ivanhoe Mines reported a 6.5% quarterly decline in production at the world’s newest large copper mine, Kamoa-Kakula in the DRC.

The tightness of the copper concentrate market has been reflected in treatment and refining charges plummeting from over $90 per ton to below $10/ton. This drastic reduction forced Chinese smelters, responsible for about half of the global refined copper production, to consider a 10% production cut.

Meanwhile, demand for copper continues to grow. Right now, the demand for copper until 2050 is twice as much as all the copper produced in human history.

While prices have reached among the highest levels in the last five years, some believe that copper and other commodities have never been more undervalued.

One thing we know for sure. The case for all commodities rests on the US dollar. Once the Fed starts cutting rates, the dollar will weaken and the whole commodity complex will strengthen.

Investing in juniors has historically been a good way to take advantage of rising metal prices.

Juniors own the world’s future mines – they help the majors replace the ore they are constantly depleting in their operating mines, and so help overcome the copper supply shortages we know are coming.

About the Vikingen

With Vikingen’s signals, you have a good chance of finding the winners and selling in time. There are many securities. With Vikingen’s autopilots or tables, you can sort out the most interesting ETFs, stocks, options, warrants, funds, and so on. Vikingen is one of Sweden’s oldest equity research programs.

Click here to see what Vikingen offers: Detailed comparison – Stock market program for those who want to get even richer (vikingen.se)